Hello blog! Its been a while. I have been thinking hard on what to blog about lately...Its been so hard for me to keep up with school work and everything else. I miss my readers. I have some information on Afro Latinos and Afro Dominicans and its about history, roots, culture, and the struggle of self acceptance. Acceptance of African Heritage. For years I felt that I MUST visit The Domini and help and just slef aware!!! Dominican republic has issues with the Afros and its really tough to quite tell you everything so I'll post the article here that I had read off of Zoe Saladana's blog that she got from a newspaper article:

Skin Deep

Current mood: optimistic

Old wounds inform clash of race and image in Dominican Republic

Candace Barbot/Miami Herald

By Frances Robles

McClatchy Newspapers

July 26, 2007

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic --Yara Matos sat still while long, shiny locks from China were fastened, bit by bit, to her coarse hair.

Not that Matos has anything against her natural curls, even though Dominicans call that pelo malo -- bad hair.

"If you're working in a bank, you don't want some barrio-looking hair. Straight hair looks elegant," the bank teller said. "It's not that as a person of color I want to look white. I want to look pretty."

And to many in the Dominican Republic, to look pretty is to look less black.

Dominican hairdressers are internationally known for the best hair-straightening techniques. Store shelves are lined with rows of skin whiteners, hair relaxers and extensions.

Racial identification here is thorny and complex, defined not so much by skin color but by the texture of your hair, the width of your nose and even the depth of your pocket. The richer, the "whiter." And, experts say, it is fueled by a rejection of anything black.

"I always associated black with ugly. I was too dark and didn't have nice hair," said Catherine de la Rosa, a dark-skinned Dominican-American college student spending a semester here. "With time passing, I see I'm not black. I'm Latina.

"At home in New York, everyone speaks of color of skin. Here, it's not about skin color. It's culture."

The only country in the Americas to break free of black colonial rule (it had been controlled by neighboring Haiti), the Dominican Republic still shows signs of racial wounds more than 200 years later. Presidents historically encouraged Dominicans to embrace Spanish Catholic roots rather than African ancestry.

Here, as in much of Latin America, the "one-drop rule" works in reverse: One drop of white blood allows even very dark-skinned people to be considered white.

As black intellectuals here try to muster a movement to embrace the nation's African roots, they acknowledge that it has been a mostly fruitless cause. Black pride organizations such as Black Woman's Identity fizzled for lack of widespread interest. There was outcry in the media when the Brotherhood of the Congos of the Holy Spirit -- a community with roots in

Africa -- was declared an oral patrimony of humanity by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

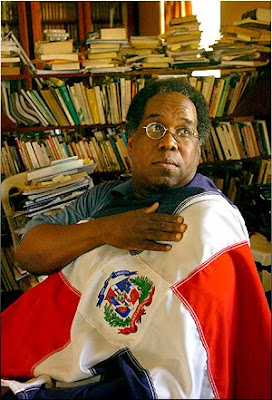

"There are many times that I think of just leaving this country because it's too hard," said Juan Rodriguez Acosta, curator of the Museum of the Dominican Man. Acosta, who is black, has pushed for the museum to include controversial exhibits that reflect many Dominicans' African background. "But then I think: Well, if I don't stay here to change things, how will things ever change?"

A walk down city streets shows a nation where black and dark-skinned people vastly outnumber white people; most estimates say 90 percent of Dominicans are black or of mixed race. Yet census figures say only 11 percent of the country's 9 million people are black.

To many Dominicans, to be black is to be Haitian. So dark-skinned Dominicans tend to describe themselves as any of the dozen or so racial categories that date back hundreds of years -- Indian, burned Indian, dirty Indian, washed Indian, dark Indian, cinnamon, moreno or mulatto, but rarely negro.

The Dominican Republic is not the only nation with so many words to describe skin color. Asked in a 1976 census survey to describe their own complexions, Brazilians came up with 136 different terms, including cafe au lait, sunburned, morena, Malaysian woman, singed and "toasted."

"The Cuban (black person) was told he was black. The Dominican (black person) was told he was Indian," said Dominican historian Celsa Albert, who is black. "I am not Indian. That color does not exist. People used to tell me, 'You are not black.' If I am not black, then I guess there are no (black people) anywhere, because I have curly hair and dark skin."

Using the word Indian to describe dark-skinned people is an attempt to distance Dominicans from any African roots, Albert and other experts said. She noted that it's not even historically accurate: The country's Taino Indians were virtually annihilated in the 1500s, shortly after Spanish colonizers arrived.

Researchers say the de-emphasizing of race in the Dominican Republic dates to the 1700s, when the sugar plantation economy collapsed and many slaves were freed and rose up in society.

Later came the rocky history with Haiti, which shares the island of Hispaniola. Haiti's slaves revolted against the French and in 1804 established their own nation. In 1822, Haitians took over the entire island, ruling the predominantly Hispanic Dominican Republic for 22 years.

To this day, the Dominican Republic celebrates its independence not from cen-turies-long colonizer Spain, but from Haiti.

"The problem is Haitians developed a policy of black-centrism and ... Dominicans don't respond to that," said scholar Manuel Nunez, who is black. "Dominican is not a color of skin, like the Haitian."

Dictator Rafael Trujillo, who ruled from 1930 to 1961, strongly promoted anti-Haitian sentiments and is blamed for creating the many racial categories that avoided the use of the word "black."

The practice continued under President Joaquin Balaguer, who often complained that Haitians were "darkening" the country. In the 1990s, he was blamed for thwarting the presidential aspirations of leading black candidate Jose Francisco Pena Gomez by spreading rumors that he was Haitian.

To some of the women who relax their hair, it's simply a way to have soft, manageable hair in the Dominican Republic's stifling humidity. But several women said the cultural rejection of African-looking hair is so strong that people often shout insults at women with natural curls.

"I cannot take the bus because people pull my hair and stick combs in it," said wavy-haired performance artist Xiomara Fortuna. "They ask me if I just got out of prison. People just don't want that image to be seen."

The hours spent on hair extensions and painful chemical straightening treatments are actually an expression of nationalism, said Ginetta Candelario, who studies the complexities of Dominican race and beauty at Smith College in Massachusetts.

"It's not self-hate," Candelario said. "Going through that is to love yourself a lot. That's someone saying, 'I am going to take care of me.' It's nationalist, it's affirmative and celebrating self."

Money, education, class -- and, of course, straight hair -- can make dark-skinned Dominicans be perceived as more "white," she said. Many black Dominicans here say they never knew they were black until they visited the United States.

"During the Trujillo regime, people who were dark skinned were rejected, so they created their own mechanism to fight it," said Ramona Hernandez, director of the Dominican Studies Institute at City College in New York. "When you ask, 'What are you?' they don't give you the answer you want ... saying we don't want to deal with our blackness is simply what you want to hear."

Hernandez, who has olive-toned skin and a long mane of hair she blows out straight, acknowledges she would "never, never, never" go to a university meeting with her natural curls.

"That's a woman trying to look cute; I'm a sociologist," she said.

Purdue University professor Dawn Stinchcomb, who is African-American, said people insulted her in the street when she traveled to the Dominican Republic in 1999 to study African influences in literature.

Waiters refused to serve her. People wouldn't help Stinchcomb with her research, saying if she wanted to study Africans, she'd have to go to Haiti.

"I had people on the streets ... yell at me to get out of the sun because I was already black enough. It was hurtful. ... I was raised in the South and thought I could handle any racial comment. I never before experienced anything like I did in the Dominican Republic.

"I don't have a problem when people who don't look like me say hurtful things. But when it's people who look just like me?"

Here's a documentary trailer that is about Afro Latinos and their hardships on what I had mentioned earlier. I'm excited for this documentary to release because it will shed light. Its releases in 2010.

YOU TELL ME WHAT YOU THINK..

http://www.worldstarhiphop.com/videos/video.php?v=wshhBGOr0ga6h4l10UZS